14th century Khirki Masjid, or ‘window mosque,’ is one of the most atmospheric Sultanate Period monuments in Delhi, but it’s not for the faint of heart. Its architecture is militaristic and foreboding, with thick walls and lots of dark enclosed space. From the outside it resembles not so much a place of worship as a fortress. This has even led people in the adjacent residential areas which have grown up within the last few decades to refer to the historical mosque as their neighborhood qila, or fort.

Unlike so many of the famous Indian mosques, Khirki Masjid features very little in the way of decorative elements. There are no delicate floral engravings or intricate calligraphical inscriptions here, just rows of unadorned sturdy columns and rubble masonry walls interrupted by perforated stone windows carved with simple grid patterns. With many historical Indian mosques, the mecca-facing qibla wall and the central mihrab, the point towards which the faithful direct their prayers, are the most decoratively embellished parts of the structure. But at Khirki masjid, almost the opposite is true. The qibla wall is practically bare, with the central mihrab residing in a dark recess. There are no windows along this side of the mosque, so the congregations who offered up their prayers here would have done so almost in darkness.

The foreboding southern entrance to Khirki Masjid as it appeared during an early morning visit in 2023. Note the padlocked gate and the patches of old plaster eroding off the exterior of the rubble masonry. One can see how this might be mistaken for the entrance to a fortress. The mosque hadn’t opened when I first showed up, so to pass the time I navigated the alleyways of Khirki Village behind it until I reached the early 16th century tomb of Yusuf Qattal.

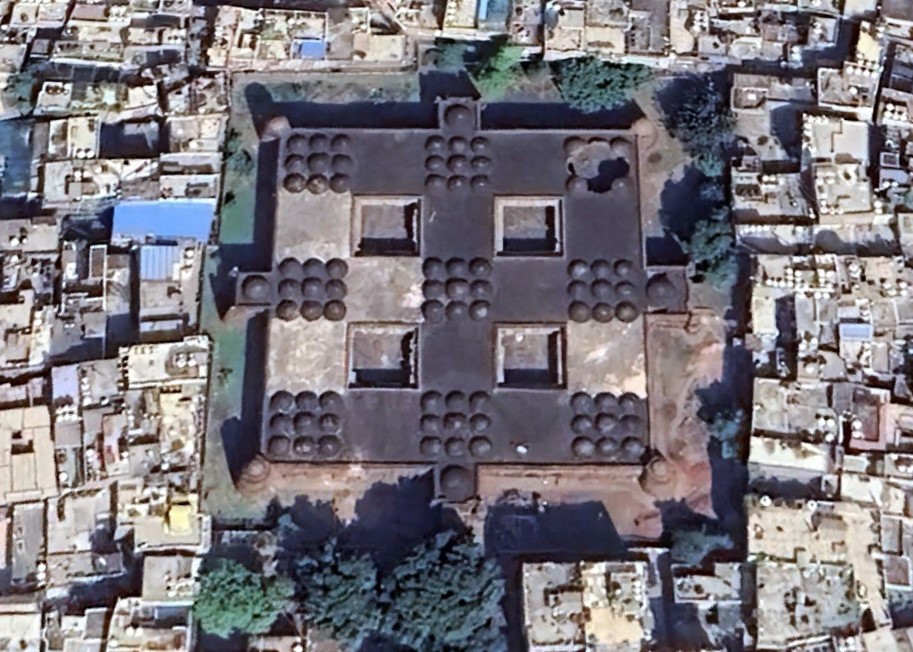

The design of the mosque is highly unusual. Almost as a rule, Indian mosques were built with wide-open courtyards so that they could hold large crowds of worshipers. But not Khirki Masjid. The structure is mostly covered by a roof held up by a grid of stone pillars. Its layout is square and can be neatly divided into 25 smaller squares. Four of these are open to the sky, forming courtyards that let in some much-needed illumination. Of the remaining 21 squares, nine are roofed with groups of small domes which have become the homes of thousands of bats, while the other twelve have been left plain. The mosque has three gates, one each on the southern, eastern, and northern side of the structure. To the west, the mosque’s central mihrab is housed in a projecting false gate. At each corner are four small turrets.

Satellite imagery of Khirki Masjid showing the layout of the structure and the groups of domes on the roof. The alternating light and dark patches seem to be the result of recent restoration activity. Note the collapsed roof section on the northeast corner. I’ve never found a source which explained exactly how long ago this collapse occurred. According to news articles from 2023, the Archeological Survey of India intends to renovate that section of the roof. Hopefully they’ll do a decent job, though I’ll believe that when I see it. Previous restoration attempts in other parts of the mosque were so inept that the work was halted by horrified conservationists. Long story short, shoddy workmanship involving improperly mixed lime-mortar ingredients turned a significant part of the interior of the mosque a hideous shade of pink. Perhaps the bad press that ensued from that restoration attempt will ensure this one is handled with more care.

Khirki Masjid is thus fascinating, architecturally impressive, and deeply atmospheric. But what it isn’t is pretty. In this respect the mosque is representative of the other surviving monuments of its era, the reign of the Turkic Tughluq dynasty in Delhi. It was constructed in the 1370s, during the rule of Firoz Shah, the third Tughluq sultan. Firoz Shah is regarded as among the greatest builders in Delhi’s history, who commissioned not only Khirki Masjid, but an entirely new city, Firozabad, along with numerous other monuments that are now scattered across India’s capitol. But he is also viewed as a conservative religious reformer. While his predecessor, the eccentric, controversial, Muhammad bin Tughluq briefly extended his reign over the majority of the subcontinent, Firoz Shah reigned over a dominion that was much reduced. Unlike Muhammad bin Tughluq, who is thought to have been more religiously tolerant than his predecessors (though this is debatable), Firoz Shah repressively imposed strict Sharia law. He battled against various uprisings around the fringes of his kingdom and was concerned primarily with maintaining a remnant of the Tughluq domain, rather than expanding outwards. Under his rule, Delhi was a regional power rather than a vast empire, and Firoz Shah was more conservationist than conqueror.

The architect, Firoz Shah’s prime minister Khan Jahan Junan Shah, likely designed Khirki Masjid to be in keeping with the strict interpretation of Islam that was practiced among the Tughluq ruling elite. The result is a place of worship that comes across as, more than anything else, severe.

A corner turret of Khirki Masjid, still quite early in the morning. In the past few decades, the surrounding village has grown both in population density and in height. Now the residential buildings loom high over the monument. I suspect the wall of buildings only serves to further cut off sunlight that would otherwise be entering through the mosque’s many small windows. Khirki Masjid may not literally be a fortress, but it does seem as though its walls are holding modern Delhi at bay. Note the exceedingly mean looking fence at the lower lefthand corner topped with nasty hooked spikes. That’ll keep the monkeys out…

A view along the northern side of the mosque, towards the northwestern turret. Here you can get some sense of how the ground level around the building has risen since the 14th century. The arched openings at the base of the mosque were where the ground was located six centuries ago. To reveal them in modern times a moat had to be dug around the foundation of the monument. This only reinforced the notion that the structure was a fort, rather than a mosque.

Inside Khirki Masjid.

At certain angles, the views through the arched stone corridors become almost disorienting.

Khirki Masjid isn’t only remarkable for its history and architecture. It’s also a prime habitat for some of Delhi’s surprisingly abundant and varied urban wildlife. The 14th century structure is a refuge for over 10,000 bats which roost in dark chambers underneath the mosque or under the domes in the roof. It’s possible to observe several large colonies in the shadows on the northern side of the structure, clinging in great furry chattering mats to the ceiling. I’ve probably seen more bats in a single trip to Khirki Masjid than in all the rest of my life combined.

A vast hanging bat colony on the underside of one of the ceiling domes. This is only one of several domes, mostly on the northern side of the monument, which have been colonized. People who are squeamish about small chattering mammals…which is most people…might find a sight such as this a tad off-putting.

In 2023 I had come to Khirki Masjid twice before, and so had witnessed the huge bat colonies in years past. But I was unsure if I would be seeing them again this time around. After covid, I thought the Delhi civic authorities might have decided to clear the bats out on public health grounds. Personally, I find the seething mammalian carpets in the old mosque fascinating. They add immeasurably to the atmosphere of the place. But…they also smell really bad. Large sections of the floor plan are covered in mats of bat guano. If a person is careless enough to walk directly underneath one of the large congregations of bats in the undersides of the domes, the person is showered with bat feces and urine. Not exactly a dream vacation. More atmosphere isn’t necessarily a positive thing.

There is an interesting paper on the bats in Khirki Masjid and other Delhi historical monuments called The Monumental Mistake of Evicting Bats from Archaeological Sites—A Reflection from New Delhi, by Ravi Umadi, Sumit Dookia, and Jens Rydell. The basic gist is that the bats have a variety of environmental benefits and therefore shouldn’t be evicted. The authors argue that the bats in monuments such as Khirki Masjid only do, at most, superficial damage to stonework, but perform an important public service by effectively suppressing agricultural pests.

Khirki Masjid might seem like its buried deep within the urban jungle of Delhi, but there are numerous farmer’s fields only a few kilometers away, well within the nightly flight radius of a mouse-tailed bat, the most numerous species in the mosque. The thousands of bats roosting within the 14th century building consume vast quantities of pests that would otherwise be eating valuable crops. Thus, maintaining the small mammals within the heritage structure is a net benefit to the people of Delhi.

But, rather humorously, the authors do admit that “large accumulations of bat guano and urine from bats sometimes have a strong smell, and this could indeed repel visitors.” I suspect the bats continued existence within the mosque is in doubt. The most recent restoration efforts might have scared many of them off, and I suspect that any government attempt to increase visitation by tourists would, understandably, view the bats as an impediment. They may not be there for long. This would be a pity. Maybe the bats are a bit gross and unsanitary. They’re also something a person doesn’t see every day.

As for making Khirki Masjid a more tourist friendly heritage site, bats or no bats, I suspect the mosque will never be high on visitors “must see” lists. It’s not friendly, or sublime, or even, with its thousands of stinky chattering bats, peaceful. It’s dark, creepy, claustrophobic, and a clear product of a violent and unsettled era. It’s spartan architecture and unadorned interior is the exact opposite of the colorfully complicated exuberance so many foreign visitors expect from India.

But I like it.

Bats!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting me on my Patreon page. There, you can download an extended edition of my book The Green Unknown which includes several chapters available exclusively on Patreon.

One thought on “Delhi Overlooked Part 2: Khirki Masjid”